Kanhoji Angre :- AS HE RESISTED ENGLISH SOLDIERS AND RULERS ,HE WAS CALLED A PIRATE BY THE ENGLISH

kunjali markkar resised porchuguese navv and was called a PIRATE BY THE ENGLISH

Kunhali Marakkar I or Mohammed Kunjali Marakkar (also known as Kunhali Marakkar) was a Kunhali Marakkar (Muslim naval chief) of the Samoothiri Raja, a Hindu king of Kozhikode (anglicized Calicut), in present day state of Kerala, India during the 16th century. He was the first of the four Kunjalis who played a part in the Raja's naval wars with the Portuguese, who arrived in India in 1498. The Marakkars are credited with organizing the first naval defence of the Indian coast, to be later succeeded in the 18th century by the Maratha Sarkhel Kanhoji Angre. The title of Marakkar was given by the Raja. It may have been derived from the Malayalam word marakkalam meaning ‘boat,’ and kar, a termination, showing possession.The four key Marakkars: The title of Marakkar was given by the Raja. It may have been derived from the Malayalam word marakkalam meaning ‘boat,’ and kar, a termination, showing possession.The four key Marakkars:- Kutty Ahmed Ali - Marakkar I

- Kutty Pocker Ali - Marakkar II

- Pattu Kunjali - Marakkar III

- Mohammed Ali - Marakkar IV

|

Origins

According to tradition, Marakkars were originally marine merchants of Kochi who left for Ponnani in the Samoothiri Raja's dominion when the Portuguese came to Kochi. They offered their men, ships and wealth in the defence of their motherland to the Samoothiri of Kozhikode-The Raja took them into his service and eventually they became the Admirals of his fleet. Another version suggests that they were merchants of Cairo who settled in Kozhikode and joined the Samoothiri's navy. Of the four Marakkars, Kunjali Marakkar II is the most famous. Another version suggests that they were merchants of Cairo who settled in Kozhikode and joined the Samoothiri's navy. Of the four Marakkars, Kunjali Marakkar II is the most famous. |

Portuguese

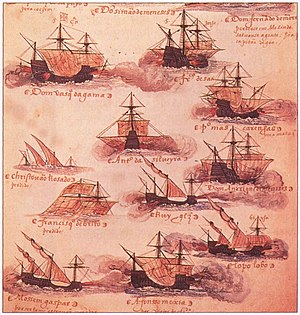

The Portuguese initially attempted to obtain trading privileges in 1498, but soon had troubles because the pressure from the Arabs over the Raja, since they had traditionally been trading in his ports, and did not want to lose the monopoly in trading spices. The Raja resisted these attempts which resulted in the Portuguese trying to destabilise his rule by negotiating a treaty with his arch enemy, the Kingdom of Kochi in 1503. Sensing the Portuguese superiority at sea, the Raja set about improving his navy. He appointed Kunjali to the task.

The fight between the Raja and the Portuguese continued on until the end of the 16th century, when the Portuguese convinced the Raja in 1598 that Marakkar IV intended to take over his Kingdom. The Raja then joined hands with the Portuguese to defeat Marakkar IV, ending in his defeat and death in 1600.

|

Key events

The staircase captured from a Portuguese Ship on the event of one of Marakkar’s victory over Portuguese. Madonna can be seen engraved on it. It is kept in the Kottakkal juma masjid and used as a platform during the ‘juma’ prayer.  The sword used by the last Kunjali Marakkar at the mosque at Kottakkal, Vadakara - 1498 - Raja builds a fort at Ponnani.

- 1500 December - Raja expels Portuguese from Kozhikode.

- December 24, 1500 - Portuguese (led by Pedro Álvares Cabral) take refuge at port of Kochi, where the King offers them spices.

- 1501 January - Portuguese conclude a treaty with Tirumulpad, the King of Kochi, allowing them to open a feitoria there.

- 1503 - Portuguese crown the new King of Kochi, effectively making him a vassal of the King of Portugal.

- 1503 March - Samoothiri Raja attacks foe Hindu Kingdom of Kochi, also known as Perumpadapu Swaroopam.

- 1503 - Portuguese Afonso de Albuquerque arrives in Kochi to find it destroyed, and after helping in the defense of the king, manages to obtain permission to build a fort. Thus the first European fort is built in India by 1505 called Fort Manuel or Manuel Kotta.

- 1505 November - murder of the Portuguese factor António de Sá, the other Portuguese men and the destruction of the church of St. Thomas in Kollam.

- 1506 - Samoothiri Raja now approached Raja of Kolathiri. The Portuguese had behaved contemptuously to the Muslims at Kannur, and so Raja of Kolathiri also intended to teach them a lesson. The Raja laid siege the St. Angelos fort at Kannur. But the Portuguese won this battle, and the Raja of Kolathiri was forced to plea for peace.

- 1506 - Raja's naval forces join the Turkish and Arab navies to defeat the Portuguese navy led by D. Lourenço de Almeida, son of the Portuguese Viceroy. However, Portuguese repel the attack.

- November 14, 1507 - Portuguese under Almeida attacked Ponnani.

- 1508 March - Sultan of Cairo's navy defeats Portuguese at Battle of Chaul, killing D. Lourenço de Almeida

- 1509 February - Portuguese counter attack and defeat the Samoothiri's forces and the Mamluk Egyptian/Turkish Navy at the Battle of Diu. Turks and Egyptians withdraw from India, leaving the seas to the Portuguese.

- 1513 - Raja and Portuguese sign a treaty giving Portuguese right to build a fort at Kozhikode, in return for their assistance in the Raja's fight with the Kingdoms of Kochi and Kolathiri.

- 1520? - Assassination attempt on Raja

- 1524 - King of Portugal re-sends Vasco Da Gama back to India to control the Raja.

- February 26, 1525 - Portuguese navy led by new Viceroy Menezes raids Ponnani, but the Raja defeats them with assistance from Tinayancheri, and Kurumliyapatri.

- 1530 - Formation of Chalium (also known as Challe, now Chaliyam) fort by Portuguese - the Raja of Vettattnad enabled the Portuguese to erect a fort at Chalium at the mouth of the Beypore river. Chalium was a strategic site, for it was only 10 km south of Kozhikkode. Raja of Chaliyam or Parappanad also helped the Portuguese.

- 1540 - Samoothiri Raja entered into an agreement with the Portuguese and stopped the war. Treaty allows the Portuguese a trade monopoly at Kozhikode port.

- 1550 - Portuguese attacked, pillaged and plundered Ponnani. They set fire to several houses and four mosques, including the Valia Palli.

- 1569-1570 - War between the Portuguese and Samoothiri's forces at Chaliyam fort. The battle of Talikota in 1565 in which Vijayanagar, the ally of the Portuguese, was defeated, emboldened the Samoothiri to start large scale operations against the Portuguese.

- 1571 September 15 - Portuguese lose the war and surrender Chaliyam fort. Samoothiri Raja destroys the fort.

- 1573 - Pattu Marakkar (Kunjali III) obtained permission from Samoothiri to build a fortress and dockyard at Puthupattanam. This fort later came to be called the Marakkar Kotta (Marakkar Fort).

- 1584 - Samoothiri Raja needed free navigation without the passes of the Portuguese, to the ports of Gujarat, Persia and Arabia, to continue his trade. So an agreement with the Portuguese is made. The sanction to the Portuguese to build a factory at Ponnani is given. By now the Raja has clearly shifted his policy towards the Portuguese.

- 1586 - Marakkars defeat the Portuguese in a naval battle.

- 1588 - The Portuguese settle again in Kozhikode with the Samoothiri's permission.

- 1589 - Marakkars inflict a crushing defeat on the Portuguese.

- 1591 - Samoothiri Raja allows the Portuguese to build a factory at Kozhikkode. He lays the foundation stone of their church and grants them the necessary land and building materials. His commanders like Kunjali III who were sworn enemies of the Portuguese were ignored again. Kunjali III begins to distance himself from Samoothiri.

- 1595 - Kunjali IV becomes the Chief of the Marakkars. Marakkar, who had been given the powers and privileges of any Nair noble in the Samoothiri's service, strengthens the fortress at Kottakal and openly challenges his master by styling himself as the "Lord of the Indian seas". He cuts off the tail of one of Samoothiri's elephants and ill treats a Nair noble and his wife, who had been sent to get his explanation for the deed.

- 1598 - The rebellion by his vassal exasperates the Samoothiri, who joins up with the Portuguese and fights Kunjali Marakkar IV. The first joint operation goes very bad for the allies, owing to a lack of communication between the Portuguese and the Samoothiri. They suffer heavy losses.

- 1600 - In the second battle, the Samoothiri attacks Marakkar Kotta from the land with an army of 6000 and the Portuguese navy under André Furtado bombards it from the sea. Left with no choice, Kunjali Marakkar surrenders to Samoothiri on a solemn promise of pardon, but the Samoothiri breaks his word and hands his former Admiral over to the Portuguese, who executes him and his men, after taking them to Goa.

|

|

my comment:-i have seen centuries old muslim settlements in Mumbai-one near worli sea face and one near juhu beach NEAR HOTEL SEA PRINCESS .on enquiry they claimed they are from malabar and settled in Bombay/Mumbai since centuries.I dont know whether famous quawal singer Aziz Naznan who is also a Marakkar; settled in Mumbai; is related to original Marakkars from malabar or not.

RELATED READING ON Google :-

(1) PIRATES MALABAR(Blog/Maddy- MARCH 3 2011)-read on google

MALABAR HILL 19TH CENTURY |

|

|

| VIEW FROM MALABAR POINT OF THE HILL 1850'S |

MALABAR POINT:-Malabar Point, an astounding geographical location rises imperiously over land, the headland juts into the panoramic harbour like a cape in the cerulean sea.

In times past, the azure skies would forecast plunder as the sails of marauders appeared, the dreaded pirates of Malabar.

They would ascend the pinnacle to plan their pillage. This summit by the shores heralded a view of the emerging city. Prophesying their recurring piracy, the peak came to be known as Malabar Point.

PIRATES (REAL) AND INDIAN FREEDOM FIGHTERS- NEAR BOMBAY:-

Kanhoji Angre :- AS HE RESISTED ENGLISH SOLDIERS AND RULERS ,HE WAS CALLED A PIRATE BY THE ENGLISH

v Battles

1702 - Seizes small vessel in Cochin with six Englishmen

1706 - Attacks and defeats the Siddhi of Janjira

1710 - Captures the Kennery (now Khanderi) islands near Bombay after fighting the English vessel, Godolphin for two days

1712 - Captured the yacht of the British President of Bombay, Mr. Aislabie, releasing it only after obtaining a hefty ransom of Rs. 30,000

1713 - Ten forts ceded to Angre by English

1717 - English ships bombard Kennery island and Angre signs treaty with Company paying Rs. 60,000

1718 - Blockaded Bombay port and extracted ransom

1720 - English attack Vijaydurg (Gheriah), unsuccessfully

1721 - English and Portuguese jointly attack Alibagh, but are defeated

1723 - Angre attacks two English vessels, Eagle and Hunter

The Western Naval command of the Indian Navy was named INS Angre on 15 September 1951 in honour of the valiant sea commander. A statue of him exists at the old Bombay Castle located within the enclave located at the Naval Dockyard, South Mumbai.

KUNJALI MARIKKAR - [WAS CALLED A PIRATE BY ENGLISH AND PORTUGUESE RULERS BECAUSE HE RESISTED THE FOREIGN RULERS ]

The four Kunjali Marakkars and their tenure:

- Kutti Ahmed Ali – Kunjali Marakkar I (1520 – 1531)

- Kutti Pokker Ali – Kunjali Marakkar II (1531 – 1571)

- Pattu Marakkar – Kunjali Marakkar III (1571 – 1595)

- Mohammed Ali – Kunjali Marakkar IV (1595 – 1600)

Ancestral home of Kunjali Marakkar at Iringal, Kottakkal, near Calicut, now preserved as a Museum.

Origins of Marakkar

According to tradition, the

Kunjali Marakkars were maritime merchants of Arab decent who supported the trade in the Indian ocean who settled in the coastal regions of Kayalpattinam, Kilakarai, Kulasekarapatnam, Nagore and Karaikal. They intermarried between Mukkuvas and Maravar tribes. But they shifted their trade to Kochi and then migrated to Ponnani in the Zamorin's dominion when the Portuguese fleets came to Kingdom of Cochin. They offered their men, ships and wealth against the Portuguese to the Zamorin of Calicut-the king took them into his service and eventually they became the Admirals of his fleet.

The Kunhali Marakkar or Kunjali Marakkar

was the title given to the (Muslim naval chief) of the Samoothiri Raja, a Hindu king of Kozhikode (anglicized Calicut), in present day state of Kerala, India during the 16th century.

They offered their men, ships and wealth in the defence of their motherland to the Samoothiri of Kozhikode-The Raja took them into his service and eventually they became the Admirals of his fleet.

- 1586 - Marakkars defeat the Portuguese in a naval battle.

- 1588 - The Portuguese settle again in Kozhikode with the Samoothiri's permission.

- 1589 - Marakkars inflict a crushing defeat on the Portuguese.

Mayimama Marakkar

Battle of Chaul - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Battle_of_Chaul

The Battle of Chaul was a naval battle between the Portuguese and an Egyptian Mamluk fleet in 1508 in the harbour of Chaul in India. The battle ended in a Mamluk victory. It followed the Siege of Cannanore in which a Portuguese garrison successfully resisted an attack by Southern Indian rulers.3 ships and 5 caravels: 6 Egyptian carracks and ...

Marakkar had initially been a Muslim merchant who had had a dispute with the Raja of Cananor, and following a complaint of the Raja had been gravely mishandled by the Portuguese Captain Vicente Sodré. He had held a desire for revenge since then.[3]

He was killed in the 1508 naval encounter at Chaul.[3]

my comment:-i have seen centuries old muslim settlements in Mumbai-one near worli sea face and one near juhu beach NEAR HOTEL SEA PRINCESS .on enquiry they claimed they are from malabar and settled in Bombay/Mumbai since centuries.I dont know whether famous quawal singer Aziz Naznan who is also a Marakkar; settled in Mumbai; is related to original Marakkars from malabar or not.

INS Kunjali-Indian Navy establishment at Mumbai

The Indian Navy shore-based naval air training center at Colaba, Mumbai is named Naval Maritime Academy INS Kunjali II in honour of the second Marakkar

The Indian Navy shore-based naval air training center at Colaba, Mumbai is named Naval Maritime Academy INS Kunjali II in honour of the second Marakkar

The Kunjali Marakkar Memorial erected by the Indian navy at Kottakkal, Vatakara

Inscriptions on the Kunjali Marakkar Memorial at Kottakkal, Vatakara

.......................................................................................................................................................

CAPT KIDD, THE REAL PIRATE NEAR BOMBAY 1N 1700'S:-

'Byron' wrote

." Kidd's destination was Madagascar and the mouth of the Red Sea. Being unsuccessful in accomplishing the end he had been sent on, i.e., the destruction of the pirates and their settle- ments, or from whatever other reason, he made for the coast of India, Cochin and Calicut, and throwing off" all trammels, he attacked the ships he had come out to protect, and gave up the role of privateer ! He spared no nationality. All was fish that came to his net, and his appetite grew on what it fed, until gorged with the plunder, as he admits himself, of £100,000 (£250,000 nowadays).

In 1697, when Kidd was at Jinjheera,

https://www.quora.com/Is-Malabar-Hills-of-Mumbai-anyhow-related-to-Ma...

To quote from Malabar Hill and the Pirates of Malabar "The original name of the ... from a place near Thalassery in Malabar ( Northern Kerala) had owned land ..

Yes

it is. The relation is not clear but it's in connection with the

Zamorin pirates of Malabar who ruled the waters and had been known to

attack Mumbai as well. To quote from Malabar Hill and the Pirates of Malabar "The original name of the Malabar hill, point area was Shrigundi. The story is described thus: Shri-Gundi

is called Malabar Point after the pirates of Dharmapatan (That is near

Tellichery – Curious!), Kotta, and Porka on the Malabar Coast, who, at

the beginning of British rule in Bombay, used to lie in wait for the

northern fleet in the still water in the sea of the north end of Back

Bay."Written Apr 24, 2014 • View Upvotes

Probably the earliest depiction of Canonore town , from 1572 Date: first Latin edition of volume I was published in 1572. After: an

unidentified Portuguese manuscript."

[An

early woodcut bird-eye's view of the town of Calicut. India] Plant et

Figure de la riche cit� de Calecut en la premiere Inde.

Author: Belleforest, F. de.

PlaceAndYear: Paris, 1575.

Description: Francois de Belleforest (1530-1583). Edited a French

edition of Sebastian M�nster's 'Cosmography', named 'La Cosmographie

universelle', 1575. An early woodcut bird-eye's view of the town of

Calicut as seen from the sea, with ships in the foreground and right a

ship's yard.

See also

these two Indian naval chiefs were called pirates by colonial rulers from portugal and england

https://books.google.co.in/books?id=1PVMMoChwY4C

Rajaram Narayan Saletore - 1978 - India

It was realised that, if their piracy was not checked and those ships not ... all the pirate chieftains of the South were the Malabar pirates of the Kunhali family, ... a place on the Kerala coast, two miles north of Trikkodi, in the Meladi Amsam, .

blog.calicutheritage.com/2009/.../pirates-in-history-of-calicut-calicut.htm...

Apr 27, 2009 - A Source book on early medieval Kerala History. We are proud to announce ... Calicut's association with piracy on the high seas is as old as piracy itself. Piracy was .... But, who were the 'Malabar pirates'? Is it a reference to ...

Popular Posts

-

After the disastrous tsunami of 2004,

researchers have been digging into the past to document all cases of

possible tsunamis which ...

-

Charles Baudelaire Courtesy Wikipedia

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) was a French Romantic poet who is

considered as a pioneer among the...

-

A view of the Jews Street with shops at the

far end It was young Thoufeek Zakriya, a history enthusiast, avid

blogger ( http://jewsofm...

-

One Hundred Years of a local Logan

Logan’s Malabar Manual (1887) has inspired many of his successors to

study the customs, traditio...

-

What was Calicut like before the Zamorins

established thier rule in the 12 th century? We have only folklore

masquerading as history to...

-

The Silk Route (red) and traditional

coastal spice route (blue) courtesy: Wikipedia When Vasco Da Gama

reached the shores of Calicut, ...

-

We are proud to announce the publishing of

Calicut Heritage Forum's President, Prof. MGS Narayanan's classic work,

Perumals of K...

-

The Black Hole of Attingal - The Story of A

Forgotten Massacre Generations of students all over the English

speaking world were fed on th...

-

Early this year, I was invited to participate

in a lively discussion at the Nalanda Srivijaya Centre of the Institute

of South East Asian ...

-

A 17th Century engraving of vasco Da Gama

Although Gama was feted in Lisbon as the conqueror of the east, he was

still seething with ager at...

Pirates in the History of Calicut

Calicut pops up in the most unlikely stories. Business Standard reports that many of the victims of the Somalian piracy now raging in the Gulf of Aden are seamen from Calicut!

Incredibly,

India is reportedly the biggest trading partner of the lawless Somalia,

supplying it with essential commodities like rice, pulses, wheat, flour

and sugar and helping transport the country's only significant export -

goats. The trade is undertaken in large dhows, many of them made in

Beypore. And the brave seamen who undertake the trade come from Mumbai,

Kutch, Mangalore and - Calicut.

And

while high profile attacks on Russian and US ships and tankers get

world attention and swift naval action, these anonymous victims are

often at the mercy of the dhow owners and small time traders of Dubai

who would rather cut their losses than spend more money as ransom.

Calicut's

association with piracy on the high seas is as old as piracy itself.

Piracy was recognised as one of the occupational hazards of seafaring.

As Biddulph explained, 'There was no peace in the ocean. The sea was a

vast No Man's domain where every man might take his prey'.

As

trade flourished so did piracy. The Indian trade with the Red Sea was

paid for in gold and silver and, therefore, ships sailing from Jeddah -

which carried pilgrims from Mecca, apart from the treasure - were prime

targets. Many of these vessels were bound for Calicut.

British

government took several measures to contain piracy on the Indian seas.

Countries were required to issue passes and East India Company

Commissioners were authorised to seize pirate ships and hold them till

the King's pleasure.

But

all these measures did not diminish the threat from pirates, and ships

bound for the Malabar coast -extending from bet Dwarka in Gujarat to

Anjengo in Travancore - were plagued by frequent and violent attacks

by buccaneers. A specimen of the viciousness of such attacks is provided

in the following narration of what happened off the coast of Calicut

during such a raid:

23rd november 1696

On this

morning a ship under English colours stood into Calicut, and when

alongside ship struck the English and hoisted Danish colours, fired a

broadside, boarded and took her. Her boats then took three other ships.

The Governor then came to us with threats and ordered us forthwith to

send off to her and ask who they were, whereupon we sent Captain Mason,

who returned saying that they were soldiers of fortune and that if the

ships were not ransomed for Pounds 10,000 they and the rest of the

shipping should be burned. We were well guarded all that night by the

Governor's people.

24th November 1696

This morning

the pirate was found to have moved her prizes to deeper water. The

Governor ordered us to send off to know if they could lessen their

demands. Captain Mason was accordingly sent off with a flag of truce and

remonstrated civilly but to no purpose. They said he was no countryman

of theirs, that they would not abate of 40,000 dollars ransom, and that

unless it was sent off by noon one of the ships would be fired. Captain

Mason again went off and offered 20,000 dollars, but they were deaf to

it, and at four o'clock set one ship on fire.

It

was clear by now that the local Governor (presumably representing the

Zamorin) was buying time with the English pirates while arranging for an

assault by 'Malabar pirates'. The assault started in the night of 25th

November. By the evening of 26th November the English pirates had been

driven away and the Malabar pirates also managed to rescue Captain

Mason, who had been held hostage by the pirates.

27th November 1696

Captain Mason

returned, having been put in a boat by the English pirate which was

captured by the Malabar pirates, whereby he was obliged to jump

overboard and swim ashore. He brought news that the pirate would cruise

for Persia and Bussors ships. He reported her to be of about 300 tons,

20 guns and 100 men, her captain a Dutchman of New York, and that she

daily expected a consort of about the same strength under one Hore. They

offered him command of the ship if he would join them. He

gathered that most of the pirates were fitted out from New York and

returned thither to share the plunder with the Governor's connivance.

One pirate had presented the Governor with his ship.

War

with France was raging and there was no way the English naval force

could come to the rescue of its merchant fleet. It was thus that some

influential persons in London including the Chancellor, Lord Somers,

Lord Orford and Lord Bellomont (who had been designated the Governor of

New York)formed a syndicate and obtained a letter of marque for

privateering to tackle the menace of piracy. It was rumoured that King

William himself had a ten per cent share in the syndicate.

They

obtained a commission for Captain William Kidd to act against the

pirates with a reward of 50 pounds for every captured pirate. But soon

it was revealed that Kidd had other ideas. From a tormentor of pirates

he turned out to be the biggest pirate of them all, attacking English,

French, Dutch and native ships without discrimination. His activities on

the Malabar coast hurt English trade interests most and soon the entire

'syndicate' episode turned into a stinking political scandal.

Captain

Kidd had visited Calicut in October 1697, apparently to seek

replenishment of 'wood and water', but his reputation had preceded him

and the Company authorities politely refused him, although he tried to

browbeat them with authority of the King's Commission. Turned away from

Calicut, Kidd sailed on towards the Laccadives. His last daring act was

the capture of the ship Queddah Merchant.

Fate

caught up with Kidd and he was arrested at the behest of his own

mentor, Lord Bellomont who had by then taken over as the Governor of New

York. The good Lord who had shared of Kidd's booty tried to distance

himself from the pirate, claiming that 'I secured Captain Kidd last

Thursday in the Gaol of this Town (Boston) with five or six of his

men... It was true the King had allowed me a power to pardon pirates.

But that I was so tender of using it (because I would bring no stain on

my reputation) that I had set myself a rule never to pardon piracy

without the King's express leave and command'. This pompous statement

came after Bellomont snatched from Kidd the only piece of evidence (the

French pass issued to Queddah Merchant) which could have saved Kidd's

life!

Perhaps

Bellomont was hinting to the King that he could bail out his former

business partner. But this did not happen and Kidd was tried, convicted

and hanged at Execution Dock (on the Thames, at Wapping) on 23rd May

1701. If there was honour among thieves, it was only Kidd who

demonstrated it - he did not disclose the names of his powerful patrons,

despite close questioning!

While

all this was happening, the Zamorin was the powerful Bharani Thirunal

(1684-1705) who has been described as 'the terror of the Dutch'. He was

perhaps still stationed in Ponnani and even found time to conduct two

Mamankams in 1694 and again in 1695.

The

Governor mentioned in the narration of pirate attack must have been the

Kozhikkode Thalachannavar who must have been the de facto Governor of

Calicut. But, who were the 'Malabar pirates'? Is it a reference to some

local naval force which must have been restructured after the cruel

betrayal of Kunhali Marakkar? Or did the Shahbandar Koya have his own

rapid action force?

Reference:

1. Business Standard, 15 November 2008

2. Dictionary of Pirates - Jan Rogozinski

3. The Pirates of Malabar etc. - John Biddulph

4. The Zamorins of Calicut - K.V. Krishna Ayyar

5

comments:

maddy06.blogspot.com/2011/.../malabar-hill-and-pirates-of-malabar.htm...

Mar 13, 2011 - They state thus - Bombay became the target of the sea pirates that also included the ones from Kerala's Malabar Coast. So, in order to ensure ...

A cursory look at the name of one of the costliest bits of real estate

in Bombay (nowadays called Mumbai) signifies its relationship to the

South West coastal area of Malabar. There is a reason to that, and I

thought I would cover that interesting bit of history for the benefit of

all, mainly to erase the typical distorted description provided in many

a book and website.

They state thus - Bombay became

the target of the sea pirates that also included the ones from Kerala’s

Malabar Coast. So, in order to ensure the protection from any type of

pirates attack near the hill, a lookout tower was founded. It was meant

for keeping an eye on the pirates and the sea as well. Later this hill

came to be known as ‘Malabar Hill’, which is very popular today.

The Raj Bhavan site says -

In times past, the azure skies would

forecast plunder as the sails of marauders appeared, the dreaded

pirates of Malabar. They would ascend the pinnacle to plan their

pillage. This summit by the shores heralded a view of the emerging city.

Prophesying their recurring piracy, the peak came to be known as

Malabar Point.

Was that right? To figure it out let us go back to the 16th

century when the Portuguese attempts at colonizing India were at its

peak. It was a period signified by systematic attempts at subduing the

traders and trade that had been conducted from Malabar. Starting with

Vasco Da Gama’s arrival at Calicut in 1498, the Portuguese strengthened

their presence in Cochin, Goa, Surat and Bombay on the west coasts. The

only resistance they faced initially was the sea based forays from the

Kunhali Marakkar and his able seamen of South Malabar. The Marakkars had

until then been running the Malabar trade (mainly food grains) with the

blessings of the King of Cochin and the Zamorin of Calicut, but once

their livelihood was threatened, they rose up in arms. I must hasten to

add here that piracy indeed existed on the Malabar Coast and has many a

time been attributed to moors, but it was sporadic, and not organized.

Details of such old acts of piracy can be found in the accounts of many a

travel writer, including Ibn Batuta and others.

Then again it is said that Malabar hill was

where they conducted a pilgrimage to the Banaganga tank and Walkeshwar

temple. Now that is an oddity by itself, the Moplah pirates praying to a

heathen idol? That would not be quite right, isn’t it? A detailed study

was needed, though the answer was apparent, that the term Malabar

pirates was far-flung and widespread and applied to a wide variety of

armed seafarers not quite pleased with the foreign usurpers making merry

in the west coast towns, people who conducted much trade over sea

routes and plying ships laden to the brim with the riches of India.

Indeed the opportunist cum pirate decided to attack these slow moving

and lightly armed ships. Who were they? Were they from Malabar-Kerala in

the fist place?

While

the Zamorin took on the Portuguese armies on land, the Kunhalis and

their men engaged in sea based skirmishes with the Portuguese ships. The

method of using many organized small boats to attack a flotilla soon

became very effective and went on for a period of 70 years 1530 – 1600

till the Dutch came by and the Kunhale family was gone. The ships used

by Kunhali’s men, the war-paroe, was a small craft manned by just 30-40

men each, and could be rowed through lagoons and narrow waters. Several

of these crafts were deployed at strategic points in the Malabar coast

and they would emerge from small creeks and inconspicuous estuaries,

attack the Portuguese ships at will, inflict heavy damage and casualties

by setting fire to their sails and get back into the safety of shallow

waters. And thus people who were traders soon became attackers. So were

they pirates, corsairs or privateers? If you look at history books, the

moors of Malabar, the Kunhali led seamen have been called Corsairs and

pirates. Check out the definition towards the end of this article, and

based on that I would take the direction towards privateers in this case

for they had the blessings of the Zamorin in fighting the Portuguese.

So as you can see, they were an armed force

at the command of the Zamorin’s admiral and thus were more privateers

or corsairs, but not pirates. Now that the first point has been

established, they were the earliest form of an Indian ‘regional’ navy

fighting against the invading Portuguese, in hindsight. Later there were

others involved in the fray notably Tanoji Angre, his son Kanhoji Angre

(early 18th century) or Conajee Angria and his ships, which were included collectively in the term Malabar pirates.

What were the Kunhali’s of Malabar doing in

the Bombay area? Logically, where they not restricted to the Malabar

Coast by language, and the large distance of some 700-800 miles?

Consider that the Marakkars used small pattemars or Malabar paros (small

boats 10 paces long, rowed with oars of cane and had a mast of cane)

for their warfare and sailing them to such distances was not routinely

possible. Bigger dhows were indeed used for piracy, but the Marakkar

ship would be too far from the home base and would never venture more

than 70 miles of their Ponnani towns, from earlier descriptions. So one

can safely assume that the Malabar pirates, termed so by the British,

were closer in origin to Bombay.

Now with the Marakkar & Malabar seamen

mostly out of the equation, let us get back to Bombay to find out who

these pirates actually were, starting from the 1600’s. By 1600, the last

of the Kunhali Marakkars were gone from Malabar. With it organized

navies of Calicut virtually became defunct though some Moplah’s

continued on, as locally based pirates sporadically attacking slow

merchant ships.

Between 1534 and 1661, Bombay was under Portuguese occupation. By

the middle of the 17th century the growing power of the Dutch Empire

forced the British to acquire a station in western India. On 11 May

1661, the marriage treaty of Charles II of England and Catherine of

Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal, placed Bombay in

possession of the British Empire, as part of dowry of Catherine to

Charles. In 1661, Bombay was finally ceded to the British.

By

the time Shivaji came on the scene against the British occupation,

Bombay was already in the hands of the British. His navies came into

picture by 1670 and were part of the collective called the Malabar

pirates. Kanhoji Angre came a little later, towards 1700-1723 and his

attacks or forays against British and Portuguese ships were directed all

the way South to Cochin as well as Northwards to Bombay. Collectively

there two and their navies were the major constituent’s of the so called

‘Malabar pirates’. Both these families are well covered in history

texts, so I will let them lie in peace there for the time being, and get

back to the high seas, back to when Kunhali the 4

th was killed and

Dom Pedro a.k.a Ali Marakkar took over until 1620. Thana was infested with pirates according to Marco Polo as early as 1290. In the 15

th

century it is mentioned in Nikitin’s travels that the pirates were

mainly Hindu signifying the Marathas from Junnar. One such pirate chief

was Shankar Rao of Vishalgarh. The main lot was a ragtag group of

Guajarati corsairs, Moghul Seedees and Dutch sea thieves, until the 1600

period

But

between 1600 and 1670, there were a number of attacks around Bombay, so

who were these so called pirates? Upon perusing Salvatore’s Indian

pirates, one is led to believe that the pirates termed Malabari pirates

comprising various sorts (Guajarati – Cambay, Malabar and European)

seized rich booty near Diu & Goa as well as Cochin in the 1600-1610

periods. This is perhaps Ali Marakkar’s doing. By this time English

pirates had also entered the scene and Chaul in Konkan was their HQ.

Pyrard Della Valle was the first to collectively call them Malabar

pirates for according to him Malabar encompassed the coast line between

Bombay to Cape Comorin. Later accounts by Mandelso also document that

the Paroes of Malabar mainly attacked ships around the Cochin area and

Cannanore. This signifies that Panthalayani kollam or Calicut port was

by now dead. The rest of the period comprised only some rag tag piracy.

Polo, in the 13th century, said however that the pirates were a brotherhood ‘From this kingdom of Malabar, from

the kingdom of Thana, and from another near it called Guzerat, there

go forth every year more than a hundred corsair vessels on cruise. These

pirates take with them their wives and

children, and stay out the whole summer. Their method is to join in

fleets of twenty or thirty of these pirate vessels together, and they

then form what they call a sea cordon - that is, they drop off till

there is an interval of five or six miles between ship and ship, so that

they cover something like 100 miles of sea, and no merchant ships can

escape them. For when any one corsair sights a vessel a signal is made

by fire or smoke, and then the whole of them make for this, and seize

the merchants and plunder them. But now the merchants are aware of this,

and go so well manned and armed, and with such great ships, that they

don't fear the corsairs. Still mishaps do befall them at times." "The

people of Guzerat," says the same traveller, "are the most desperate pirates in

existence, and one of their atrocious practices is this: when they have

taken a merchant vessel they force the merchants to swallow a stuff

called tamarind, mixed in sea-water, which produces a violent purging.

This is done in case the merchants, on seeing their danger, should have

swallowed their most valuable stones and pearls, and in this way they

secure the whole." The sacred island of Beyt, in the Gulf of Cutch, off

the north-west corner of the peninsula of Kattywar, was better known as

"the Pirates' Isle," and the inhabitants of the Land's End of the peninsula were noted for their audacity as sea-rovers.

But by 1670 we see the Sajanian pirates of

Kathiawar Gujarat followed by the Marathas. The leaders Shivaji and his

progeny were organized in their fight against the Portuguese. But to

lord them all later came the Maratha commodore of Shivaji’s fleet named

Kanhoji Angre. He had a control over the seashore some 240 miles long

between Bombay & Vengurla. By 1710-1729 he controlled the shores

effectively ad humiliated the British at every given chance. He was

succeeded by his son Sambhaji who continued in the same vein until 1734

and then it was Toolaji Angre. The British finally retaliated with might

and by 1756; had finally destroyed most of the Angre holdings. It was

thus Angre and his seamen who were the so called ‘Malabar pirates’ of

the 18th century, while the British ruled Bombay.

So we saw the various types of Guajarati

and Maratha privateers or pirates, whatever one may term them were

harassing the British on the seas. But why did they venture onto the

land? What is the connection with Malabar hill? It is said that they

came to that side of the rocks, sheltered from the winds, waiting for

commercial shipping to pass by after ascending

the pinnacle to scan, watch the skyline and plan their pillage. This

peak came to be known as Malabar Point and the hillock, Malabar hill.

William hunter was another one to generalize the Malabar pirates into

one group holding the sea coast from Bombay to Cape Comorin. He mentions

about their plunders on shore while Pyrard mentions they would never

attack anybody on shore.

As legends go, both Shivaji and Angre used

to visit Banaganga for a holy dip and Walkeshwar for the festivals and

prayers. But there were also Europeans amongst the Malabar pirates. As

it is written “If the pirates were but Arabs or Malabars, matters had not been so bad; but European pirates were abroad, indulging in

unheard-of excesses, seizing Mughal pilgrim ships (the Gunsway or

Ganjasawai), and leading to the incarceration of our leaders and

servants at Surat.”

The original name of the Malabar hill, point area was Shrigundi. The story is described thus: Shri-Gundi

is called Malabar Point after the pirates of Dharmapatan (That is near

Tellichery – Curious!), Kotta, and Porka on the Malabar Coast, who, at

the beginning of British rule in Bombay, used to lie in wait for the

northern fleet in the still water in the sea of the north end of Back

Bay. The name Shri-Gundi apparently means the Lucky Stone. At the very

extremity of Malabar Point is a cleft rock, a fancied yoni, to which

numerous pilgrims resort for the purpose of regeneration by the efficacy

of a passage through this sacred emblem. The yoni or hole is of

considerable elevation among rocks of no easy access in the stormy

season incessantly surf-buffeted. Women as well as men pass through the

opening. You descend some steps on rugged rocks. Then thrusting your

hands in front you ascend head first up the hole.

The

Banaganga tank story has Lord Rama, after a long and thirsty trek in

search of Sita, stopped at Sri Gundi and supposedly fired an arrow into

ground to get water (somehow connected to Ganaga as well) , and so it

ended up a sacred tank, after which he built a sand idol (Walk eashwar)

to worship. The original temple built around this idol was destroyed by

the Portuguese, but the temple was rebuilt again in 1715 by Rama Kamath.

Shivaji Maharaj when close to death is said to have landed at Malabar Point

and passed through the rock, probably to free him from the haunting

presence of the murdered Afzulkhan. Kanhoji Angria (1690-1730) is said

to have visited Bombay by stealth to go through the hole at the Malabar Point. By 1670, the English built a government house in Malabar point, but the place was so poorly fortified that (it is said) the Malabar pirates often

plundered the native villages and carried off the inhabitants as

slaves. The English soon loaded the terraces with cannon and built

ramparts over the bowers. There they housed two great guns to get the

pirate ships.

As James Douglas rambles about the pilgrimage of the pirates

In

the pre-Portuguese days the pilgrims, i.e., "the Malabars," would land

at Mazagon, or at a small haven near our Castle which the English on

their arrival called Sandy Bay, or, in the fair season, at what is our

present Wood Wharf in Back Bay, convenient enough and right opposite the

steep ascent.

Here buggalow and

pattamar would discharge their cargo of "live lumber" or faithful

devotees, as you are disposed to view them. Now they proceed to breast

the “ Siri," halting, no doubt, at the Halfway House, where the Jogi

would give them a drink from his holy well. Here they would have time to

draw their breath, chew betelnut, or say their prayers. Thence,

refreshed, to the summit, and now along a footpath studded with palmyra

palms, sentinels by sea and land on the ridge, and very much on the

track of the present carriage road, they make their way to those old

pipal trees at our "Reversing Station," old enough in all conscience to

have sheltered Gerald Aungier and the conscript fathers of the city from

the heat of the noonday sun, and how much older we know not.

And

now they descend the brow of the hill, pass the site of the present

Walkeshwar temple, past the twisted trees in the Government House

compound,—of the existence of which we have indubitable evidence as far

back at least as 1750.

And here we may remark that the Malabar

Hill of these days was much more wooded than at present. When land is

left to itself, everything grows to wood. It is so in Europe, and it is

so here, as we can see with our eyes in that magnificent belt of natural

jungle which clothes the slopes down to the water's edge of Back Bay

(and which reminds one of the Trossachs on an exceedingly small scale),

where, among crags and huge boulders, the leafy mango and the feathery

palm assert themselves out of a wild luxuriance of thick-set creepers

glowing with flowers of many colours. The hare, the jungle fowl, and the

monkey were doubtless no strangers to these bosky retreats. At length

the temple, ornate with many a frieze and statue, bursts upon the view

amid a mass of greenery. Black it is, for the Bombay trap becomes by

exposure to innumerable monsoons like the Hindu pagodas among the orange

groves of Poona. And now, the journey ended, the white-robed pilgrims,

and some forsooth sky-clad in the garb of nature, bow their faces to the

earth, amid jessamine flowers, in the old temple of Walkeshwar, on its

storm-beaten promontory, with no sound on the ear save the cry of the

sea-eagle, or the thud of the waves as they dash eternally on the beach.

Keyi’s and the ownership of Malabar Hill

Wikipedia makes an interesting mention of

the Keyi’s of Malabar and connects it to Malabar hill. It is said that

the Keyis had to sell Malabar Hill to the EIC to safeguard their

business holdings. Quoting the entry - The well known and prominent Keyi family of North Malabar in Kerala was founded by Chovvakkaran Moosa in

the early 18th Century. He was a strong force in trade and commerce

during that time, having powerful links with rulers, kings and

countries. He started off his business with the Portuguese, the French,

and the British. He owned a large part of Bombay including the area

currently known as Malabar Hill and many parts in Chowpatti Beach area.

Even today the family has some old shops and buildings in that area.

When the British East India Company started creating problems for their

business, they had to call a truce with them in order to survive. The

Keyis tried everything from funding Tipu Sultan and Pazhassi Raja in

their war with the British at the time. When everything failed, they

donated the entire area now known as Malabar Hill to the East India

Company to maintain the Keyis' trading rights in the North Malabar area. Hence the name, Malabar Hill for this Western India prime property.

I certainly could not find any

corroborating evidence for the above claim even after extensive research

and after reading KKN Kurup’s complete work on the Keyi family. While

they may have held land space around Malabar hill in the 18th

century, the name Malabar hill goes back to 1673 when Fryer wrote first

mentioned the place. Aluppi’s nephew Moosa kakka who built a bigger

fortune and may have perhaps possessed land in Bombay, came to fame only

by the early 18th century. So by conjuncture, Keyi’s do not appear to be the reason for the naming of Malabar Hill after Malabar.

In conclusion one could call this a

somewhat indiscriminate use of the term Malabar as we know it today,

though another who likes arguments would retort saying that Malabar

itself is nebulous, it was first coined in antiquity by some Arab sailor

for the coastal area of Western India between Surat and Cape Comorin.

But then again we saw how the name of the hill eventually came about,

even if by mistake and remained so, for it was finally a locale where

the pirates stopped for a lookout or for good luck and to pray

obeisance.

References

Indian Pirates RJ Salvatore

The pirates of Malabar John Biddulph

Bombay and western India: a series of stray papers, Volume 2 James Douglas

The Great Pioneer in India, Ceylon, Bhutan & Tibet

Stirring stories of peace and war, by sea and land James Macaulay

A handbook for travelers in India, Burma and Ceylon John Murray

Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Volume 26, Part 3

Guide to Bombay: historical, statistical, and descriptive James Mackenzie Maclean

The Missionary herald, Volume 89 American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

Keyis of Malabar – KKN Kurup

Definitions:

Corsaire is the term used by the French for what in English is a privateer. A Privateer was an armed ship

under papers to a government or a company to perform specific tasks.

The men who sailed on a privateer were also called privateers. Most

importantly, the famous "Articles of Piracy" often did not apply to a

ship of privateers. Often privateers were simple merchant marines who

were engaged in acts of war for profit. Other time they were hired

mercenaries. Privateers, unlike pirates were quite open about what they

did and were typically considered heroes by their host nations. In the

loosest terms, any of the above can be a pirate. If a privateer is

fighting for another country, you would probably consider him a pirate.

Anyone who robs at sea is and was a pirate. When privateers exceeded the

bounds of their commission, they became pirates. By definition, a

pirate is any person committing criminal acts against public authority,

on the high seas outside the normal jurisdiction and laws of any state

(country). By law, they can be arrested, prosecuted, and sentenced by

any state that captures them. Also, by definition, the criminal act is

of a private nature, that is personal gain, and not for political

reasons.

================

================

The

Pirates

of Malabar,

and

An

Englishwoman in India Two Hundred Years Ago

by John Biddulph  (1907)

===========

== *Introduction

by FWP*

== *Views

of the Malabar Coast*

== *Author's

preface*

*Chapter

I: The Rise of European Piracy in the East*

Portuguese pirates-- Vincente Sodre--

Dutch pirates--

Royal filibustering-- Endymion Porter's venture-- The Courten

Association--

The Indian Red Sea fleet-- John Hand-- Odium excited against the

English

in Surat-- The Caesar attacked by French pirates-- Danish

depredations--

West Indian pirates-- Ovington's narrative-- Interlopers and permission

ships-- Embargo placed on English trade-- Rovers trapped at Mungrole--

John Steel-- Every seizes the Charles the Second and turns

pirate--

His letter to English commanders-- The Madagascar settlements--

Libertatia--

Fate of Sawbridge-- Capture of the Gunj Suwaie-- Immense

booty--

Danger of the English at Surat-- Bombay threatened-- Friendly behaviour

of the Surat Governor-- Embargo on European trade-- Every sails for

America--

His reputed end-- Great increase of piracy-- Mutiny of the Mocha

and Josiah crews-- Culliford in the Resolution-- The London

seized by Imaum of Muscat

*Chapter

II: Captain Kidd*

Measures to suppress piracy-- The Adventure

fitted out-- Warren's squadron meets with Kidd-- His suspicious

behaviour--

He threatens the Sidney-- Waylays the Red Sea fleet-- Captures

the Mary--

Visits Carwar and Calicut-- His letter to the factory-- Chased by

Portuguese

men-of-war-- Chases the Sedgwick-- Chivers-- Action between Dorrill

and Resolution-- Kidd captures the Quedah Merchant--

Dilemma

of European traders at Surat-- Their agreements with the authorities--

Experience of the Benjamin-- News of Kidd's piracies reaches

England--

Despatch of squadron under Warren-- Littleton at Madagascar-- Kidd

sails

for New York-- Arrested and tried-- His defence and execution-- Justice

of his sentence-- His character-- Diminution of piracy-- Lowth in the Loyal

Merchant-- Act for suppression of piracy-- Captain Millar

*Chapter

III: The Rise of Conajee Angria*

Native piracy hereditary on the Malabar

coast--

Marco Polo's account-- Fryer's narrative-- The Kempsant-- Arab and

Sanganian

pirates-- Attack on the President-- Loss of the Josiah--

Attack on the Phoenix-- The Thomas captured--

Depredations

of the Gulf pirates-- Directors' views-- Conajee Angria-- Attacks

English

ships-- Destroys the Bombay-- Fortifies Kennery-- Becomes

independent--

Captures the Governor's yacht-- Attacks the Somers and Grantham--

Makes peace with Bombay-- His navy-- Great increase of European and

native

piracy

*Chapter

IV: An Active Governor*

Arrival of Mr. Boone as Governor-- He

builds ships

and improves defences of Bombay-- Desperate engagement of Morning

Star

with Sanganians-- Alexander Hamilton-- Expedition against Vingorla--

Its

failure-- Hamilton made Commodore-- Expedition against Carwar-- Landing

force defeated-- Successful skirmish-- Desertion of Goa recruits--

Reinforcements--

Landing force again defeated-- The Rajah makes peace-- Hamilton resigns

Commodoreship-- A noseless company-- Angria recommences attacks--

Abortive

expedition against Gheriah-- Downing's account of it-- Preparations to

attack Kennery

*Chapter

V: The Company's Servants*

The Company's civil servants-- Their

comparison

with English who went to America-- Their miserable salaries-- The

Company's

military servants-- Regarded with distrust-- Shaxton's mutiny-- Captain

Keigwin-- Broken pledges and ill-treatment-- Directors' vacillating

policy--

Military grievances-- Keigwin seizes the administration of Bombay-- His

wise rule-- Makes his submission to the Crown-- Low status of Company's

military officers-- Lord Egmont's speech-- Factors and writers as

generals

and colonels-- Bad quality of the common soldiers-- Their bad

treatment--

Complaint against Midford-- Directors' parsimony

*Chapter

VI: Expedition Against Kennery*

Sivajee's occupation of Kennery-- A naval

action--

Minchin and Keigwin-- Bombay threatened-- The Seedee intervenes--

Conajee

Angria occupies Kennery-- Boone sails with the expedition-- Manuel de

Castro--

Futile proceedings-- Force landed and repulsed-- Second landing--

Manuel

de Castro's treachery-- Gideon Russell-- Bad behaviour of two

captains--

Defeat-- Attack abandoned-- The St. George-- The Phram--

Manuel de Castro punished-- Bombay wall completed-- Angria makes

overtures

for peace-- Boone outwitted

*Chapter

VII: Expedition Against Gheriah*

Trouble with the Portuguese-- Madagascar

pirates

again-- Loss of the Cassandra-- Captain Macrae's brave

defence--

The one-legged pirate-- Richard Lazenby-- Expedition against Gheriah--

Mr. Walter Brown-- His incompetency-- Gordon's landing--

Insubordination

and drunkenness-- Arrival of the Phram-- General attack--

Failure--

The Kempsant's alliance-- Attack on Deoghur-- The Madagascar pirates,

England

and Taylor-- Ignominious flight-- Fate of the Phram-- Brown

despatched

south again-- The pirates at Cochin-- They take flight to Madagascar--

Their rage against Macrae and England-- England marooned-- Taylor takes

Goa ship-- Rich prize-- Governor Macrae

*Chapter

VIII: Expedition Against Colaba*

Measures taken in England against

pirates-- Woodes

Rogers at the Bahamas-- Edward Teach-- Challoner Ogle-- Bartholomew

Roberts

killed-- Matthews sent to the East Indies-- Naval officers' duels--

Portuguese

alliance-- Expedition against Colaba-- Assault-- Defeat-- A split in

the

alliance-- Plot against Boone-- His departure-- Matthews' schemes-- His

insulting behaviour-- He quarrels with everybody-- Goes to Madagascar--

The King of Ranter Bay-- Matthews goes to Bengal

*Chapter

IX: A Troubled Year in Bombay*

Loss of the Hunter galley--

Quarrel with

Portuguese-- Alliance of Portuguese with Angria-- War with both-- A

double

triumph-- Portuguese make peace-- Angria cowed-- Matthews reappears--

Trouble

caused by him-- He returns to England-- Court-martialled-- The last of

Matthews

*Chapter

X: Twenty-six Years of Conflict*

The case of Mr. Curgenven-- Death of

Conajee Angria--

Quarrels of his sons-- Portuguese intervention-- Sumbhajee Angria--

Political

changes-- Disaster to Bombay and Bengal galleys-- The Ockham

beats off Angria's fleet-- The Coolees-- Loss of the Derby--

Mahrattas

expel Portuguese from Salsette-- Captain Inchbird-- Mannajee Angria

gives

trouble-- Dutch squadron repulsed from Gheriah-- Gallant action of the Harrington--

Sumbhajee attacks Colaba-- English assist Mannajee-- Loss of the Antelope--

Death of Sumbhajee Angria-- Toolajee Angria-- Capture of the Anson--

Toolajee takes the Restoration-- Power of Toolajee-- Lisle's

squadron--

Building of the Protector and Guardian

*Chapter

XI: The Downfall of Angria*

Toolajee fights successful action with

the Dutch--

He tries to make peace with Bombay-- Alliance formed against him--

Commodore

William James-- Slackness of the Peishwa's fleet-- Severndroog--

James's

gallant attack-- Fall of Severndroog-- Council postpone attack on

Gheriah--

Clive arrives from England-- Projects of the Directors-- Admiral

Watson--

Preparations against Gheriah-- The Council's instructions-- Council of

war about prize-money-- Double dealing of the Peishwa's officers--

Watson's

hint-- Ships engage Gheriah-- Angrian fleet burnt-- Fall of Gheriah--

Clive

occupies the fort-- The prize-money-- Dispute between Council and

Poonah

Durbar-- Extinction of coast piracy-- Severndroog tower

*An

Englishwoman in India Two Hundred Years Ago*

*Index*

================================================

(1907)

===========

== *Introduction

by FWP*

== *Views

of the Malabar Coast*

== *Author's

preface*

*Chapter

I: The Rise of European Piracy in the East*

Portuguese pirates-- Vincente Sodre--

Dutch pirates--

Royal filibustering-- Endymion Porter's venture-- The Courten

Association--

The Indian Red Sea fleet-- John Hand-- Odium excited against the

English

in Surat-- The Caesar attacked by French pirates-- Danish

depredations--

West Indian pirates-- Ovington's narrative-- Interlopers and permission

ships-- Embargo placed on English trade-- Rovers trapped at Mungrole--

John Steel-- Every seizes the Charles the Second and turns

pirate--

His letter to English commanders-- The Madagascar settlements--

Libertatia--

Fate of Sawbridge-- Capture of the Gunj Suwaie-- Immense

booty--

Danger of the English at Surat-- Bombay threatened-- Friendly behaviour

of the Surat Governor-- Embargo on European trade-- Every sails for

America--

His reputed end-- Great increase of piracy-- Mutiny of the Mocha

and Josiah crews-- Culliford in the Resolution-- The London

seized by Imaum of Muscat

*Chapter

II: Captain Kidd*

Measures to suppress piracy-- The Adventure

fitted out-- Warren's squadron meets with Kidd-- His suspicious

behaviour--

He threatens the Sidney-- Waylays the Red Sea fleet-- Captures

the Mary--

Visits Carwar and Calicut-- His letter to the factory-- Chased by

Portuguese

men-of-war-- Chases the Sedgwick-- Chivers-- Action between Dorrill

and Resolution-- Kidd captures the Quedah Merchant--

Dilemma

of European traders at Surat-- Their agreements with the authorities--

Experience of the Benjamin-- News of Kidd's piracies reaches

England--

Despatch of squadron under Warren-- Littleton at Madagascar-- Kidd

sails

for New York-- Arrested and tried-- His defence and execution-- Justice

of his sentence-- His character-- Diminution of piracy-- Lowth in the Loyal

Merchant-- Act for suppression of piracy-- Captain Millar

*Chapter

III: The Rise of Conajee Angria*

Native piracy hereditary on the Malabar

coast--

Marco Polo's account-- Fryer's narrative-- The Kempsant-- Arab and

Sanganian

pirates-- Attack on the President-- Loss of the Josiah--

Attack on the Phoenix-- The Thomas captured--

Depredations

of the Gulf pirates-- Directors' views-- Conajee Angria-- Attacks

English

ships-- Destroys the Bombay-- Fortifies Kennery-- Becomes

independent--

Captures the Governor's yacht-- Attacks the Somers and Grantham--

Makes peace with Bombay-- His navy-- Great increase of European and

native

piracy

*Chapter

IV: An Active Governor*

Arrival of Mr. Boone as Governor-- He

builds ships

and improves defences of Bombay-- Desperate engagement of Morning

Star

with Sanganians-- Alexander Hamilton-- Expedition against Vingorla--

Its

failure-- Hamilton made Commodore-- Expedition against Carwar-- Landing

force defeated-- Successful skirmish-- Desertion of Goa recruits--

Reinforcements--

Landing force again defeated-- The Rajah makes peace-- Hamilton resigns

Commodoreship-- A noseless company-- Angria recommences attacks--

Abortive

expedition against Gheriah-- Downing's account of it-- Preparations to

attack Kennery

*Chapter

V: The Company's Servants*

The Company's civil servants-- Their

comparison

with English who went to America-- Their miserable salaries-- The

Company's

military servants-- Regarded with distrust-- Shaxton's mutiny-- Captain

Keigwin-- Broken pledges and ill-treatment-- Directors' vacillating

policy--

Military grievances-- Keigwin seizes the administration of Bombay-- His

wise rule-- Makes his submission to the Crown-- Low status of Company's

military officers-- Lord Egmont's speech-- Factors and writers as

generals

and colonels-- Bad quality of the common soldiers-- Their bad

treatment--

Complaint against Midford-- Directors' parsimony

*Chapter

VI: Expedition Against Kennery*

Sivajee's occupation of Kennery-- A naval

action--

Minchin and Keigwin-- Bombay threatened-- The Seedee intervenes--

Conajee

Angria occupies Kennery-- Boone sails with the expedition-- Manuel de

Castro--

Futile proceedings-- Force landed and repulsed-- Second landing--

Manuel

de Castro's treachery-- Gideon Russell-- Bad behaviour of two

captains--

Defeat-- Attack abandoned-- The St. George-- The Phram--

Manuel de Castro punished-- Bombay wall completed-- Angria makes

overtures

for peace-- Boone outwitted

*Chapter

VII: Expedition Against Gheriah*

Trouble with the Portuguese-- Madagascar

pirates

again-- Loss of the Cassandra-- Captain Macrae's brave

defence--

The one-legged pirate-- Richard Lazenby-- Expedition against Gheriah--

Mr. Walter Brown-- His incompetency-- Gordon's landing--

Insubordination

and drunkenness-- Arrival of the Phram-- General attack--

Failure--

The Kempsant's alliance-- Attack on Deoghur-- The Madagascar pirates,

England

and Taylor-- Ignominious flight-- Fate of the Phram-- Brown

despatched

south again-- The pirates at Cochin-- They take flight to Madagascar--

Their rage against Macrae and England-- England marooned-- Taylor takes

Goa ship-- Rich prize-- Governor Macrae

*Chapter

VIII: Expedition Against Colaba*

Measures taken in England against

pirates-- Woodes

Rogers at the Bahamas-- Edward Teach-- Challoner Ogle-- Bartholomew

Roberts

killed-- Matthews sent to the East Indies-- Naval officers' duels--

Portuguese

alliance-- Expedition against Colaba-- Assault-- Defeat-- A split in

the

alliance-- Plot against Boone-- His departure-- Matthews' schemes-- His

insulting behaviour-- He quarrels with everybody-- Goes to Madagascar--

The King of Ranter Bay-- Matthews goes to Bengal

*Chapter

IX: A Troubled Year in Bombay*

Loss of the Hunter galley--

Quarrel with

Portuguese-- Alliance of Portuguese with Angria-- War with both-- A

double

triumph-- Portuguese make peace-- Angria cowed-- Matthews reappears--

Trouble

caused by him-- He returns to England-- Court-martialled-- The last of

Matthews

*Chapter

X: Twenty-six Years of Conflict*

The case of Mr. Curgenven-- Death of

Conajee Angria--

Quarrels of his sons-- Portuguese intervention-- Sumbhajee Angria--

Political

changes-- Disaster to Bombay and Bengal galleys-- The Ockham

beats off Angria's fleet-- The Coolees-- Loss of the Derby--

Mahrattas

expel Portuguese from Salsette-- Captain Inchbird-- Mannajee Angria

gives

trouble-- Dutch squadron repulsed from Gheriah-- Gallant action of the Harrington--

Sumbhajee attacks Colaba-- English assist Mannajee-- Loss of the Antelope--

Death of Sumbhajee Angria-- Toolajee Angria-- Capture of the Anson--

Toolajee takes the Restoration-- Power of Toolajee-- Lisle's

squadron--

Building of the Protector and Guardian

*Chapter

XI: The Downfall of Angria*

Toolajee fights successful action with

the Dutch--

He tries to make peace with Bombay-- Alliance formed against him--

Commodore

William James-- Slackness of the Peishwa's fleet-- Severndroog--

James's

gallant attack-- Fall of Severndroog-- Council postpone attack on

Gheriah--

Clive arrives from England-- Projects of the Directors-- Admiral

Watson--

Preparations against Gheriah-- The Council's instructions-- Council of

war about prize-money-- Double dealing of the Peishwa's officers--

Watson's

hint-- Ships engage Gheriah-- Angrian fleet burnt-- Fall of Gheriah--

Clive

occupies the fort-- The prize-money-- Dispute between Council and

Poonah

Durbar-- Extinction of coast piracy-- Severndroog tower

*An

Englishwoman in India Two Hundred Years Ago*

*Index*

================================================

hamletram.blogspot.com/2014/12/two-malabar-pirates-in-travancore.html

Dec 25, 2014 - This is the story of a Kolathiri prince of Kannur in Northern Kerala becoming King in Travancore,and he in turn,appointing two brothers from the ...

Arakkal Brothers as Naval Chiefs in Travancore

This

is the story of a Kolathiri prince of Kannur in Northern Kerala

becoming King in Travancore,and he in turn,appointing two brothers from

the Naval family of Arakkal in Kannur, as Naval Chiefs of Travancore-

the first team to protect the waters of Travancore,much before

Eustachius De Lannoy and Chempil Arayan.

The King was Adithya Varma,and the brothers,Mammali Kidavu and Kunjikoyamu.

Adithya

Varma was adopted from the Kolathunad,along with his brother Rama Varma

and two sisters, to the Attingal royal family,before the reigning

King,Kottayam Kerala Varma,also from Kolathunad,was assassinated on

28,August,1696.Adithya Varma did the obsequies of Kerala Varma.

It

was the time when Umayamma Rani of Attingal was ruling the Travancore

Kingdom,though,Ravi Varma had taken over the elder's position(and so,the

King) in 1685 itself.He was very weak,leading a sanyasin's life,till

his death in 1704.Ravi Varma is considered by some as the son of

Umayamma Rani.When Umayamma Rani died in July,1698,the Junior

Rani,Pururuttathi Thirunal from Kolathu Nadu became the Queen of

Attingal,since the elder sister had died within a year of the

adoption.Marthanda Varma,is believed to be the her son.The attempt to

make Adithya Varma or Rama Varma,the King ,was torpedoed by King of

Nedumangad,Kerala Varma and some of the barons.The powerful Pillai

barons,when the ship,Neptune,of East India Company wrecked in

Manakkudi,near Kanyakumari,looted the entire cargo though the agreement

between the Company and the Rani stipulated equal share of the cargo,in

the event of a ship wreck.

|

| Manakkudi |

When

Ravi Varma died in 1704,the attempt of Adithya Varma to become the King

was again thwarted by the barons,who anointed Nedumangad Kerala Varma

as the King in February,1805.Though,Adithya Varma approached,the King of

Karunagappaly,he was not in a position to help,because he had become an

ally of the Kayamkulam King,who in turn,was an ally of the Dutch.But

political pressures made the Karunagappaly King to return to his old

position, and he adopted he Junior Rani and her son,Marthanda Varma from

Attingal to Karunagapally.The Karunagappally King died in

September,1707 and the Junior Rani,Pururuttathi Thirunal,became the

Regent,making her brother,Adithya Varma,powerful.Since his family had

close relationship with the Muslim Kingdom of Arakkal,he invited Mammali

Kidavu and Kunjikoyamu in an effort to protect the commercial interests

in the Travancore coast,and to post them,he established a Naval

facility at Kadiapattanam,in Kanyakumari.

|

| Kadiapattanam |

While

the Arakkal brothers were busy organizing a naval force,Nedumangad

Kerala Varma died and his successor declared himself King of

Travancore.The Naicker of Madurai accepted him and the barons,with the

support of Madurai Force,ousted Adithya Varma from Kalkulam.As a

result,Mammali and Kunjikoyamu lost the Naval Chiefs post and they

became pirates.Though the ships which had a Dutch pass,were not required

to pay the tax,the brothers,seized ships from Kayamkulam and

Purakkad,for not paying taxes.Adithya Varma became helpless,and the

traders at Purakkad and Kayamkulam,who were furious that the Dutch pass

is not valid in Travancore,snapped ties with Travancore and approached

the British.Smelling trouble,the barons declared loyalty to Adithya

Varma,promising money to pay the arrears of tribute to Madurai,and on

their demand,Adihya Varma banished Mammali and Kunjikoyamu from

Travancore,in 1708.They were captured by the Dutch at Cochin in

December,but they managed to escape soon,with the help of the

English,who gave residence to the brothers,at Anchuthengu Factory.

|

| Thengapattanam |

We

see Mammali and Mani Kurukkal,not Kunjikoyamu,next, in 1714,three years

after their one time mentor, Adithya Varma ascending the throne,after

the death of Nedumangad King.The English,with Varma's

permission,shifted Mammali and Kurukkal to Thengapattanam.They looted

ships and levied extra tax from ships carrying Dutch pass,and once,dared

to loot the ship of the King.They disappear from history at this

point.Varma died in 1721.

The Dutch priest,Jacobus Cantervisscher,in his Letters from Malabar,has recorded that the English had encouraged Muslim pirates to loot Dutch ships.

Reference:

1.Venadinte Parinamam/K Sivasankaran Nair

2.Kulasekhara Perumals of Travancore/Mark De Lannoy

3.Letters from Malabar/Cantervisscher

.............................................................................................................................

Battle of Chaul

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[hide]

Portuguese battles in the Indian Ocean

|

|

|

|

|

The

Battle of Chaul was a naval battle between the Portuguese and an

Egyptian Mamluk fleet in 1508 in the harbour of

Chaul in

India. The battle ended in a Mamluk victory. It followed the

Siege of Cannanore (1507)

in which a Portuguese garrison successfully resisted an attack by

Southern Indian rulers. This was the first Portuguese defeat at sea in

the

Indian Ocean.

[1]

Background

Previously, the Portuguese had been mainly active in

Calicut, but the northern region of

Gujarat

was even more important for trade, and an essential intermediary in

east–west trade: the Gujaratis were bringing spices from the

Moluccas as well as silk from

China, and then selling them to the Egyptians and Arabs.

[3]

The Portuguese' monopolizing interventions were however seriously disrupting

Indian Ocean trade,

threatening Arab as well as Venetian interests, as it became possible

for the Portuguese to undersell the Venetians in the spice trade in

Europe.

Venice

broke diplomatic relations with Portugal and started to look at ways to

counter its intervention in the Indian Ocean, sending an ambassador to

the Egyptian court.

[4]

Venice negotiated for Egyptian tariffs to be lowered to facilitate

competition with the Portuguese, and suggested that "rapid and secret

remedies" be taken against the Portuguese.

[4] The sovereign of

Calicut, the

Zamorin, had also sent an ambassador asking for help against the Portuguese.

[5]

Since the Mamluks only had little in terms of naval power, timber had to be provided from the

Black Sea in order to build the ships, about half of which was intercepted by the

Hospitallers of St. John in

Rhodes, so that only a fraction of the planned fleet could be assembled at

Suez.

[3] The timber was then brought overland on

camel back, and assembled at

Suez under the supervision of Venetian

shipwrights.

[5]

Preparations

The Mamluk fleet finally left in February 1507 under

Amir Husain Al-Kurdi in order to counter the expansion of the Portuguese in the

Indian Ocean and arrived in the Indian port of

Diu in 1508 after delays subduing the city of

Jeddha.

[3] It consisted of six round ships and six great galleys called galleasses.

[3] 1500 combatants were on board, as well as the ambassador of the

Zamorin ruler of

Calicut,

Mayimama Mārakkār.

[5]

The fleet was to join with

Malik Ayyaz, a former Russian slave, who was in the service of the Sultan of

Cambay, who was naval chief and master of Diu.

[3] The fleet was also planning to join with the

Zamorin

of Calicut, and then to raid and destroy all the Portuguese possessions

on the Indian coast, but the Zamorin, who was expecting the Mamluk

fleet in 1507 had already left.

[1]

Battle

The Portuguese, under

Lourenço de Almeida, son of the Viceroy

Francisco de Almeida, were inferior in number with only a light force, and located in the nearby harbour of

Chaul.

[3] The rest had sailed north to protect shipping and fight the so- called piracy.

[3]

The Mamluks sailed into Chaul and fought for two days inconclusively

with the Portuguese, unable to board their ships. Finally, Malik Ayaz

sailed in with his own galleys. The Portuguese had to retreat and

Almeida's ship was sunk at the entrance of Chaul harbour with Almeida

aboard.

[3]

Ali Hussain returned to the port of Diu, but from that point

abandoned any further initiative on the Indian coast, his ships becoming

derelict and his crews dispersing.

[1] The Portuguese later returned and attacked the fleet in the harbour of Diu, leading to a decisive victory in the

Battle of Diu (1509).

[1]

These events would be followed by a new Ottoman intervention in 1538, with the

Siege of Diu.

See also

..

Ancestral home of Kunjali Marakkar at Iringal, Kottakkal, near Calicut, now preserved as a Museum.

Ancestral home of Kunjali Marakkar at Iringal, Kottakkal, near Calicut, now preserved as a Museum. The Kunjali Marakkar Memorial erected by the Indian navy at Kottakkal, Vatakara

The Kunjali Marakkar Memorial erected by the Indian navy at Kottakkal, Vatakara